What is the primary function of the retina?

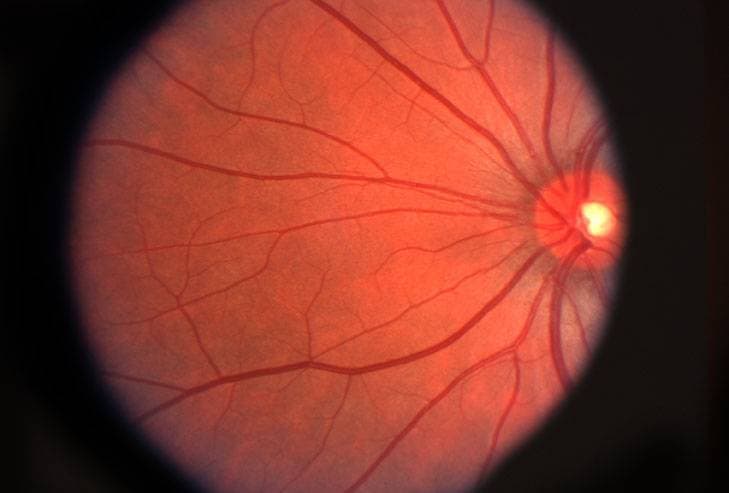

The retina is a thin layer of tissue that contains millions of light-sensitive cells (rods and cones), and is located in the back of the eye. The primary function of the retina is to receive, organize, and send visual information to your brain, through the optic nerve. This whole process enables you to see.

What is retinal disease?

Retinal diseases cause damage to any part of the retina. Untreated retinal diseases can lead to severe vision loss and even blindness. With early detection, some retinal diseases can be treated, while others can be controlled or slowed down to preserve, or even restore vision.

Symptoms of retinal disease

Many retinal diseases and conditions present with similar signs and symptoms, such as:

- Seeing floaters or flashes of light

- Blurred or distorted vision

- Blind spots in central vision

- Reduced vision

Who is at risk of developing retinal disease?

Certain factors may increase your risk of developing a retinal disease, such as:

- Age

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Eye trauma

- Family history

If you experience symptoms of retinal disease contact an eye doctor to diagnose and manage your condition.

SEE RELATED: Retinal Detachment

Most common retinal diseases

Retinal disease can present in many different forms. The most common retinal diseases, their causes, symptoms, and treatments are provided below.

1. Retinal tear

A retinal tear occurs when vitreous gel that fills the eye begins to shrink, pulling on the retina with enough force to cause the retinal tissue to tear.

As we age, the vitreous tends to separate from the retina, creating a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).

A posterior vitreous detachment affects more than 60 percent of people over age 70.

In most cases, a PVD does not cause any complications. However, some people are born with a more sticky vitreous which causes it to pull away from the retina in an abnormal way, resulting in a retinal tear.

In rare cases, a retinal tear may occur as a result of an eye injury or trauma to the retina.

A retinal tear can cause sudden vision changes, such as black spots or floaters and flashing lights. Retinal tears can increase the risk of retinal detachment and severe vision loss.

Retinal tears are typically treated with laser surgery or freezing treatments called cryotherapy.

2. Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment generally occurs when fluid travels through a retinal tear and causes the retina to detach from the other tissues in the back of the eye— cutting off its blood supply and ability to function properly.

- Retinal detachments affect 5 in 100,000 people, annually.

- Middle-aged and elderly populations are affected more frequently, with approximately 20 in 100,000, annually.

The symptoms of a retinal detachment depend on the extent of the detachment, and can vary from no symptoms at all, to seeing floaters, flashing lights, and a shadow that blocks the peripheral vision and sometimes central vision as well.

Three main causes and forms of retinal detachment include:

- Rhegmatogenous. This is the most common form— occurring as a result of a retinal tear. It may be caused by aging, or because of an eye injury, surgery, or nearsightedness.

- Tractional. This typically occurs with diabetes, when blood vessels in the back of the eye become damaged and form scar tissue. This scar tissue pulls on the retina, and leads to a detachment of the retinal tissue.

- Exudative. This occurs when fluid builds up behind your retina and pushes the retina away from the tissue attached to it from behind. It typically occurs as a result of age-related macular degeneration, injury, or retinal swelling.

A retinal detachment may be treated through laser treatments, surgery, or freezing treatments (cryotherapy) to repair any tears in the retina and to reattach the retina to the back of the eye.

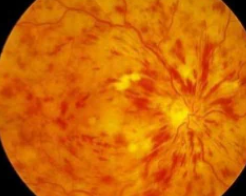

3. Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy is a serious sight-threatening complication of diabetes that can lead to blindness.

This disease is caused by high levels of sugar in the bloodstream, resulting in progressive damage to the retina.

Diabetes damages the small blood vessels throughout the body, including the tiny capillaries in the retina. Eventually, these tiny blood vessels leak blood and other fluids into the eye, and cause the retinal tissue to swell— resulting in cloudy or blurred vision. As these blood vessels are damaged, new abnormal blood vessels are produced. These new vessels are fragile and are even more susceptible to leaking and bleeding fluid into the eye.

- Diabetic retinopathy affects 1 in 3 people with diabetes.

- 95% of people with diabetic retinopathy can avoid severe vision loss with early treatment.

There are three different types of diabetic retinopathy:

- Non-Proliferative Retinopathy (NPR), also called Background Retinopathy, is the earliest stage of the disease. In this stage, high blood sugar concentration in the retina causes microaneurysms, in which damage to the walls of the tiny retinal capillaries occurs. Microaneurysms eventually rupture and bleed and due the shape, are called “dot-and-blot” hemorrhages.

- Proliferative Retinopathy (PR) is the more severe form of the disease. In this stage, abnormal blood vessels begin to grow in the retina. If these new blood vessels break, it can trigger bleeding into the vitreous, gelatinous matter that fills the eye— causing retinal scarring, severe vision difficulties, and even blindness.

- Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a complication of diabetic retinopathy. DME occurs when damaged blood vessels leak fluid into the macula— the part of the retina responsible for sharp central vision that allows you to see fine details.

- Diabetic macular edema may cause blurry or wavy vision, blind spots, and cause colors to appear dull. These symptoms can impact reading, writing, driving, and facial recognition.

Treatment of diabetic retinopathy includes anti-VEGF injections and/or laser surgery.

4. Epiretinal membrane

Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) are also known as cellophane maculopathy, or macular puckers. Epiretinal membranes are semi-translucent, fibro-cellular, and avascular— containing few or no blood vessels.

ERMs form on the inner surface of the retina, causing minimal symptoms— though sometimes, if they affect the macula, they can cause painless visual distortions and vision loss.

An ERM is made up of glial cells that grow and accumulate on the surface of the retina. The membrane resembles a wrinkled piece of cellophane, and overtime begins to contract and pull on the retina— leading to vision distortions such as blurred or crooked vision, and vision loss.

Research has shown that ERM affects up to 2 percent of patients over age 50 and 20 percent over age 75.

The most common cause of ERM is called posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), in which the retina separates from the vitreous gel— causing the retina to tear. Other causes include: retinal tears or detachment, diabetic retinopathy, CRVO or BRVO, eye trauma, eye surgery, or intraocular inflammation.

Treatment of this condition generally involves a surgical procedure called a vitrectomy.

5. Retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a rare, genetic, ocular disease that causes retinal damage and vision loss.

- RP is one of the most frequently occurring forms of inherited retinal degeneration.

- RP affects approximately 1 in 4,000 people worldwide.

In its initial stage, the retinal cells begin to degenerate in the part of the retina responsible for mid-peripheral vision— causing decreased night vision (nyctalopia), mid-peripheral visual field loss and difficulty seeing in low light. The rapid progression of the disease continues to destroy cells in the central visual field— resulting in tunnel vision, reduced visual acuity, and color vision loss.

The progression of RP causes symptoms in both eyes at a similar rate.

In its later stages, RP causes sensitivity to bright lights due to the appearance of an intense glare (photophobia) and the appearance of blinking, shimmering, or swirling lights in the visual field (photopsia).

Since RP can occur from a number of gene mutations, its progression can differ from person to person— in some cases, central vision is not affected until the person reaches 50 years, while in other cases, people experience significant loss of vision in early adulthood.

Ultimately, most individuals with RP will lose a significant amount of their vision.

There is currently no cure for RP. Many patients learn to use low vision aids that aim to magnify existing central vision to widen the field of view and eliminate glare.

6. Central vein occlusion

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is a condition that occurs when the central vein responsible for draining blood from the retina is blocked— usually as a result of a blood clot. This condition may also be caused by diabetes or glaucoma.

Central retinal vein occlusion generally presents in only one eye.

CRVO and BRVO are the second most common retinal vascular disease.

There are two different forms of CRVO:

- Non-ischemic CRVO— This is a milder form that causes retinal cells to leak, and macular edema to develop. This form does not usually present with any symptoms, though come patients complain of blurred or distorted vision. This type may also progress into the more severe form.

- Ischemic CRVO— This is a more severe form that causes the retinal cells to close off— resulting in pain, redness, irritation, and vision loss with less of a chance for restoration of vision.

Central retinal vein occlusion is typically treated with anti-VEGF injections which are used to reduce new abnormal blood vessel growth and retinal swelling. Anti-VEGF drugs include bevacizumab (Avastin®), ranibizumab (Lucentis®), and aflibercept (Eylea®).

Laser surgery may also be recommended for a more permanent treatment.

7. Branch retinal vein occlusion

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) occurs when there is a blockage in a branch of the retinal vein, as opposed to CRVO that occurs from a blockage in the central retinal vein. Branch retinal vein occlusion usually occurs as a result of a blood clot that inhibits blood drainage. Macular edema is the primary cause of vision loss associated with BRVO.

Branch retinal vein occlusion usually causes a sudden loss of vision. However, if BRVO does not affect the center of the retina, BRVO can go unnoticed.

Branch retinal vein occlusion is typically treated with anti-VEGF injections and/or laser surgery.

Retinal neovascularization is a serious complication that can occur as a result of BRVO. This condition causes an ischemia, or an inadequate blood supply to the retina— resulting in the growth of abnormal new blood vessels. These abnormal blood cells can cause a vitreous hemorrhage and further vision loss.

If this complication occurs, scatter laser photocoagulation therapy is used to stop abnormal blood vessel growth.

When to see an eye doctor

If you have noticed any changes in your vision, schedule a comprehensive eye exam as soon as possible. Through a series of tests, your eye doctor can detect any signs of ocular disease— even in its early stages.

LEARN MORE: Guide to Retinal Diseases

Caution: Seek immediate medical attention if you experience a sudden onset of floaters, flashes, or reduced vision.